Branch target prediction and performance

I was recently analyzing the performance of DIRACBenchmark after having seen a peculiar speed-up in the transition from Sandy Bridge/Ivy Bridge architecture to Haswell/Broadwell. This benchmark basically generates a long sequence of random numbers via Python random module and performs some multiply and accumulate operations. What stood out after some initial tests was a 50% improvement in runtime when switching from Xeon v2 to Xeon v3 processors. All the other benchmarks I was familiar with were showing a difference that was in the range 10%-20%, but this Python script was definitely an outlier.

Systems under test

I was comparing the performance on the following two systems:

| Ivy Bridge | Haswell | |

| CPU | Dual socket E5-2650v2 @ 2.60 GHz | Dual socket E5-2640v3 @ 2.60 GHz |

| 8 physical cores, 16 threads, 2.8GHz Turbo | 8 physical cores, 10 threads, 3.4 GHz Turbo | |

| RAM | 64 GiB DDR3, fully balanced NUMA domains | 128 GiB DDR4, fully balanced NUMA domains |

| OS | CentOS 7.3 running kernel 3.10.0-514 | CentOS 7.3 running kernel 3.10.0-514 |

| gcc | 4.8.5 | 4.8.5 |

| CPU clk | 2.00GHz, acpi_cpufreq userspace | 2.00GHz, acpi_cpufreq userspace |

The clock frequency was set to 2.00GHz via userspace governor with acpi_cpufreq

driver. Disregarding for a moment the output of the benchmark, which is not

relevant, the runtime on the two platforms was the following:

[root@ivybridge ~]# time numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 python lhcb.py

8.62366333218

real 0m58.239s

user 0 m58.007s

sys 0m0.225s

[root@haswell ~]# time numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 python lhcb.py

12.8205128205

real 0m39.315s

user 0m38.977s

sys 0m0.319sThe runtime highlights a speedup close to 50%.

Instruction set

To make sure the Python interpreter was making use of the same instruction set on both architectures, I

traced the benchmarks with Intel Software Development emulator. SDE is a dynamic

binary instrumentation tool capable of tracing the execution down to the assembly

instruction level, providing emulation support on Intel platforms for instructions

sets that are not natively supported by the hardware (e.g. it is possible to test

AVX512 code on a machine which provides only AVX2). Intel SDE is based on Pin

library, which uses ptrace system call on Linux to inject instrumentation

code into the application. Each instruction of the application is replaced with

a jmp to the instrumentation, allowing to gain control over every single

instruction executed. Clearly, this has a bearing on the runtime.

The first result obtained with SDE was a profile of the functions executed by the benchmarks. Ivy Bridge functions-breakdown, limited to the first 10 contributors, was the following:

#rank total-icount % cumulative% #times-called address function-name image-name

0: 78447041164 40.065 40.065 25000610 7fafdb921d00 PyEval_EvalFrameEx IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

1: 20255778100 10.345 50.410 0 7fafdb88b700 _Py_add_one_to_index_C IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

2: 12676220173 6.474 56.884 1 7fafdb8b07b0 PyFloat_GetInfo IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

3: 7329255341 3.743 60.627 1 7fafdb8c39f0 _PyLong_Init IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

4: 7048205162 3.600 64.227 542169587 7fafdb8b06f0 PyFloat_FromDouble IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

5: 6911426092 3.530 67.756 1 7fafcc46e310 .text IMG: /usr/lib64/python2.7/lib-dynload/_randommodule.so

6: 6048087389 3.089 70.845 2 7fafdb8adc00 Py_UniversalNewlineFread IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

7: 5218234381 2.665 73.510 34216947 7fafdaea0450 __ieee754_log_avx IMG: /lib64/libm.so.6

8: 5001235968 2.554 76.065 125029399 7fafdb8c6280 PyDict_GetItem IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

9: 4450066224 2.273 78.337 76 7fafdb8b2bb0 _PyFloat_Unpack8 IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0Haswell functions-breakdown, also limited to the first 10 contributors, was the following:

#rank total-icount % cumulative% #times-called address function-name image-name

0: 78443984168 40.061 40.061 25000613 7f547808ed00 PyEval_EvalFrameEx IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

1: 20255041770 10.344 50.406 0 7f5477ff8700 _Py_add_one_to_index_C IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

2: 12675720283 6.474 56.879 1 7f547801d7b0 PyFloat_GetInfo IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

3: 7329059493 3.743 60.622 1 7f54780309f0 _PyLong_Init IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

4: 7047863171 3.599 64.222 542143280 7f547801d6f0 PyFloat_FromDouble IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

5: 6910893488 3.529 67.751 1 7f546902d310 .text IMG: /usr/lib64/python2.7/lib-dynload/_randommodule.so

6: 6047790337 3.089 70.840 2 7f547801ac00 Py_UniversalNewlineFread IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

7: 5217908380 2.665 73.504 34214316 7f5477611450 __ieee754_log_avx IMG: /lib64/libm.so.6

8: 5001228296 2.554 76.059 125029216 7f5478033280 PyDict_GetItem IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0

9: 4450065996 2.273 78.331 76 7f547801fbb0 _PyFloat_Unpack8 IMG: /lib64/libpython2.7.so.1.0What immediately stood out from the traces above was the following:

- The two executions were pretty much identical

- The major contributor in terms of instructions executed was the Python interpreter, CPython, with

PyEval_EvalFrameEx, the core function that executes Python bytecode -

_randommodule.socontributed only for 3.5% of the total instructions, while all other contributions were mostly coming from CPython.

Results from relative comparison of instructions executed do not necessarily translate into

the same execution time comparison. It is reasonable to expect though that PyEval_EvalFrameEx is

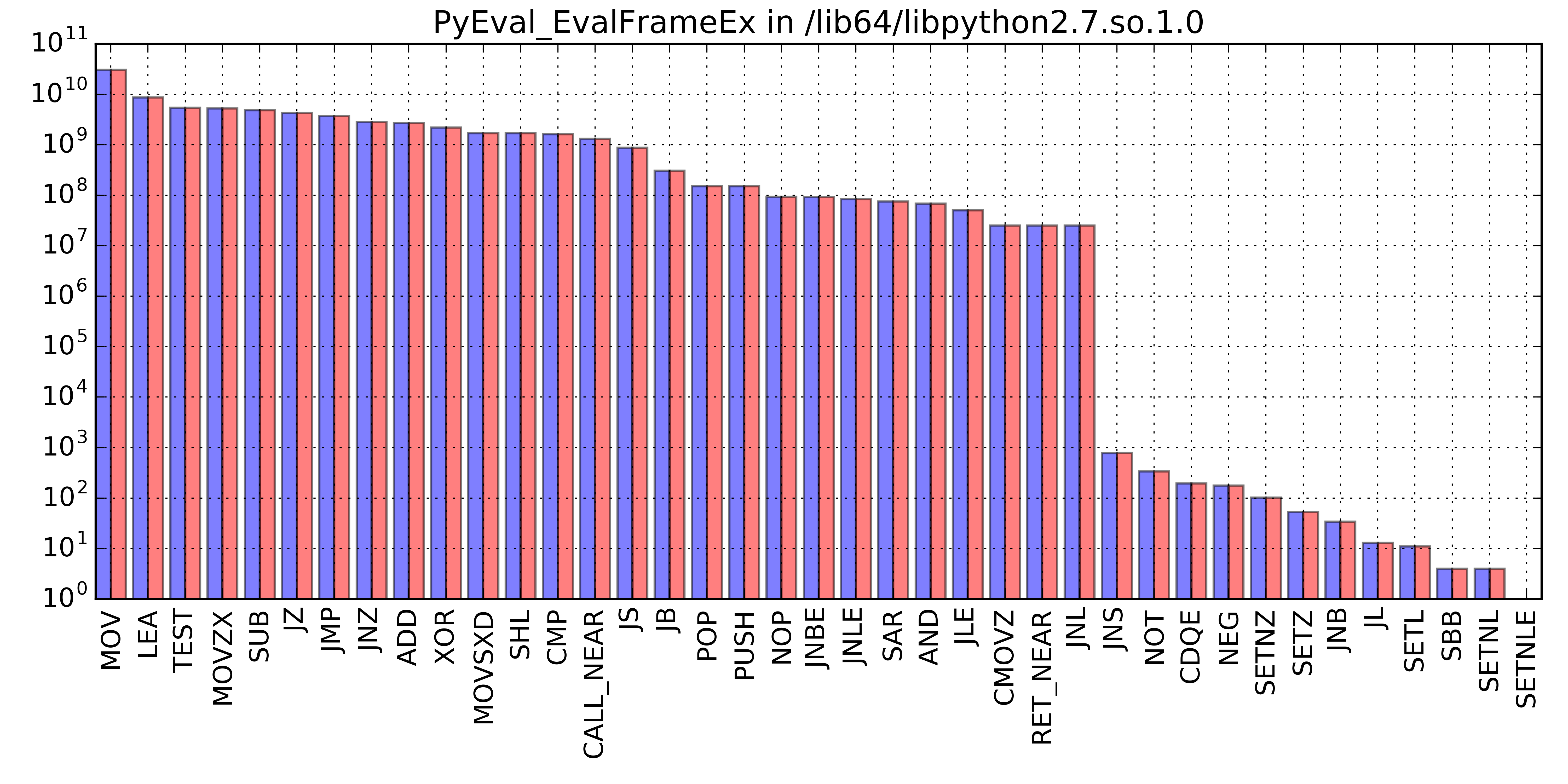

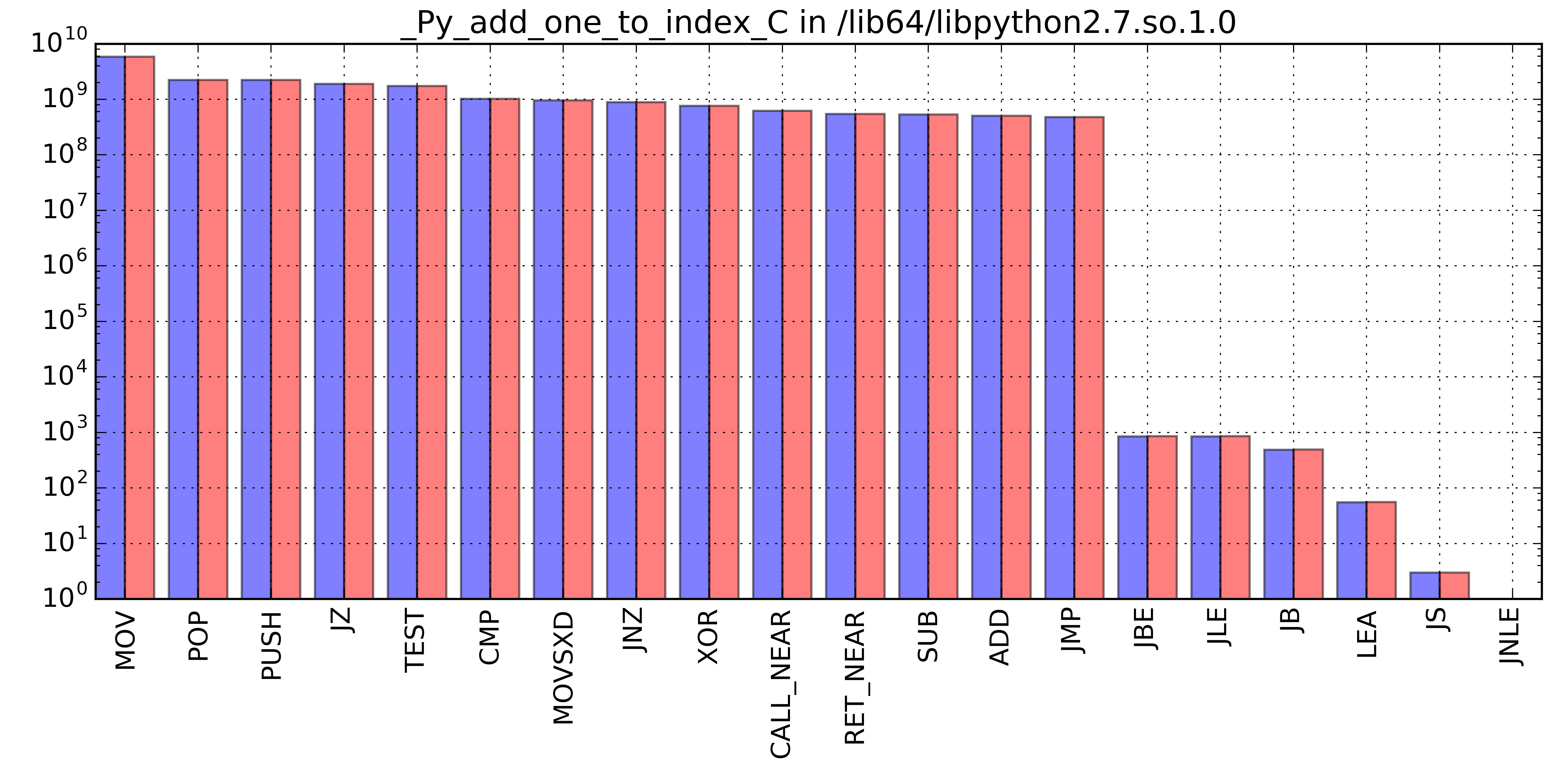

also the major contributor in terms of time. For each function sampled by SDE, I created a histogram

associating to each instruction, the number of occurrences. Two notes, before looking into the plots:

- I have restored the histograms from a previous backup and I haven’t preserved raw data. Unfortunately, these were also unlabeled, so I could not assign a posteriori the correct architecture to the red and blue lines. Nevertheless, what they suggest is that the instruction set used on Ivy Bridge and Haswell is exactly the same, so I did not go any further in rebuilding the dataset from scratch.

- I could not restore the plot for

_randommodule.so, so it is missing from the list

Given these results, I considered worthwhile having a closer look at

the main contributor, PyEval_EvalFrameEx.

Analyzing PyEval_EvalFrameEx

PyEval_EvalFrameEx is the heart of the CPython interpreter, where

bytecode is decoded and executed. Its implementation resides in

Python/ceval.c and makes use of a huge switch statement (1500 LOC)

that dispatches the current opcode to the corresponding case branch

for execution. In CPython 2.7.5, it looks like the following:

switch (opcode) {

case NOP:

<NOP Instruction>

break;

case LOAD_FAST:

<LOAD_FAST Instruction>

break;

case LOAD_CONST:

<LOAD_CONST Instruction>

break;

case STORE_FAST:

<STORE_FAST Instruction>

break;

case POP_TOP:

<POP_TOP Instruction>

break;

case ROT_TWO:

<ROT_TWO Instruction>

break;

[...]

case UNARY_CONVERT:

<UNARY_CONVERT Instruction>

break;

[...]

}Switch constructs are normally implemented in assembly with jump

tables, assigning a label to each branch which constitutes the

target of a jumps instruction when a matching argument in the switch

statement is encountered. The jump is indirect: the destination

address is loaded in a register or taken directly from memory. This

is somehow coherent with the profile of PyEval_EvalFrameEx, where

jmp is the seventh most recurrent instruction. Now, in a

further attempt to reproduce a workload that yields a 50% speedup on

Haswell architecture, I tried to write some basic code that would

replicate this indirect jmp intensive workload.

The code can be found at instr-miss-benchmark repository. The script implements a large switch statement dispatching in loop either a sequential opcode sequence or a random one. The results are as follows (the number of case branches is 512):

Ivy Bridge, sequential opcode, lenght of the sequence is 512

# perf stat numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -l 512

Performance counter stats for 'numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -l 512':

9523.964000 task-clock (msec) # 0.945 CPUs utilized

7 context-switches # 0.001 K/sec

1 cpu-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

325 page-faults # 0.034 K/sec

20,113,446,420 cycles # 2.112 GHz

9,133,199,611 stalled-cycles-frontend # 45.41% frontend cycles idle

6,205,524,997 instructions # 0.31 insn per cycle

# 1.47 stalled cycles per insn

1,347,544,552 branches # 141.490 M/sec

260,595,846 branch-misses # 19.34% of all branches

10.082002557 seconds time elapsedIvy Bridge, random opcode, lenght of the sequence is 512

# perf stat numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -r -l 512

Performance counter stats for 'numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -r -l 512':

8827.884037 task-clock (msec) # 0.912 CPUs utilized

6 context-switches # 0.001 K/sec

0 cpu-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

325 page-faults # 0.037 K/sec

19,306,672,146 cycles # 2.187 GHz

8,494,665,929 stalled-cycles-frontend # 44.00% frontend cycles idle

6,204,896,270 instructions # 0.32 insn per cycle

# 1.37 stalled cycles per insn

1,347,354,632 branches # 152.625 M/sec

257,970,218 branch-misses # 19.15% of all branches

9.677276472 seconds time elapsedHaswell, sequential opcode, lenght of the sequence is 512

# perf stat numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -l 512

Performance counter stats for 'numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -l 512':

4911.183097 task-clock (msec) # 0.983 CPUs utilized

44 context-switches # 0.009 K/sec

2 cpu-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

322 page-faults # 0.066 K/sec

9,961,459,259 cycles # 2.028 GHz

6,190,421,781 instructions # 0.62 insn per cycle

1,344,838,747 branches # 273.832 M/sec

91,048,715 branch-misses # 6.77% of all branches

4.995183920 seconds time elapsedHaswell, random opcode, lenght of the sequence is 512

# perf stat numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -r -l 512

Performance counter stats for 'numactl --physcpubind=0 --membind=0 ./branch -r -l 512':

2885.842547 task-clock (msec) # 0.998 CPUs utilized

24 context-switches # 0.008 K/sec

2 cpu-migrations # 0.001 K/sec

322 page-faults # 0.112 K/sec

5,764,806,412 cycles # 1.998 GHz

6,184,385,850 instructions # 1.07 insn per cycle

1,343,650,997 branches # 465.601 M/sec

23,396,176 branch-misses # 1.74% of all branches

2.890916053 seconds time elapsedThe comparison highlights that with a negligible delta

in the number of branches executed by the CPU, the number of branch

mispredictions is instead much higher on Ivy Bridge. A mispredicted branch is a

wrong guess taken by the front-end of the pipeline when deciding where to fetch the

next instruction. This prediction is made when fetching an instruction block: the

front-end tries to guess if the block will branch and, in this case, where it will land.

In fact, guessing the destination address is referred to as Branch Target Prediction,

as we have branching instruction (e.g. jump) which uses an indirect operand of the type:

jmp *raxThe prediction is done very early to avoid having to wait for the decode and execution stages of the pipeline. The obvious consequence is that the guess might be wrong. In that case, the instructions that have been fetched following a wrong prediction are flushed from the pipeline and the execution resumes from the correct control path.

When using a random opcode sequence of lenght 512, the number of mispredicted branches is 10 times higher on Ivy Bridge, with a difference in number of branches of only 0.2%. There is another interesting result that stands out: on Haswell, a sequential opcode sequence generates a higher number of mispredictions compared to a random one.