Reverse engineering Android 2FA OTP application

As part of my disaster recovery plan, I want to have offline backup of 2FA codes

for online banking to generate OTPs without my phone in case of emergency.

This required reverse engineering my bank’s Android OTP application, that I expected would

reveal some kind of HMAC-based HOTP/TOTP calculation. I found instead

an implementation which is significantly more complex, involving thousand of calls to

aes.Encrypt. The work presented in this post is the result of reverse engineering

smali code from the unpacked Android application, using mainly vscodium with APK lab extension.

I am not a cryptographer and this is not meant to be a security review. Some red flags did stand out to me, e.g. use of AES in ECB mode in one case, even though they do not seem to be sufficient to invalidate the security of the whole flow. However, I am still quite uncomfortable with this level of complexity for something security related, compared to a simpler RFC 6238-based TOTP. bank-otp-gen repo stores code which was written based on this reverse engineering exercise. Below, you will find some excerpts of smali code from the disassembled application, even though the focus is mostly centered around the algorithm and data flow, which were by far the most complex pieces to figure out.

High level overview

The application implements 2FA both in online and offline mode. For the former, one just needs to approve the login attempt. For the latter, a 6 digits pin is generated offline after reading a QR code provided by the backend and typing a PIN chosen when the device was enrolled. This post is focused on the second flavor of OTP generation, in particular on the algorithm for OTP calculation. I have not looked into the enrollment process, i.e. the steps that establish a shared secret between client and server.

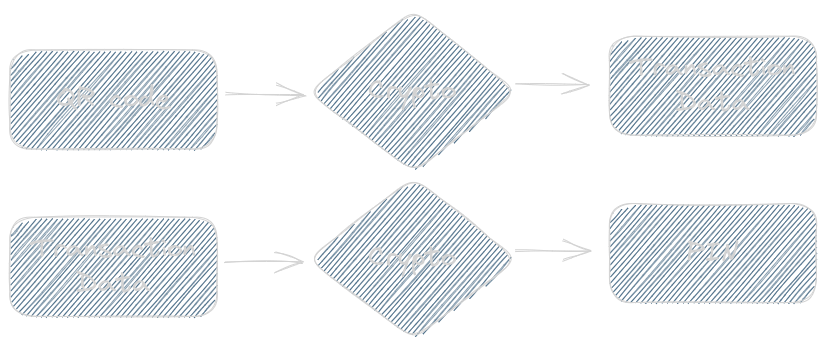

OTP generation can be broken down in two phases:

- From the QR code data, a base64 string representing “Transaction Data” is obtained

- From Transaction Data, a 6 digits OTP is obtained

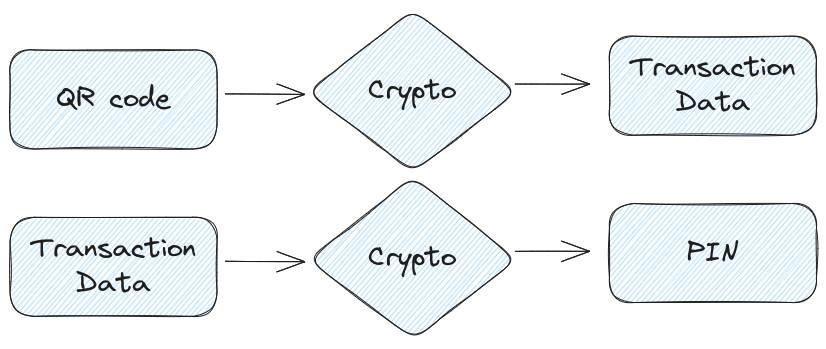

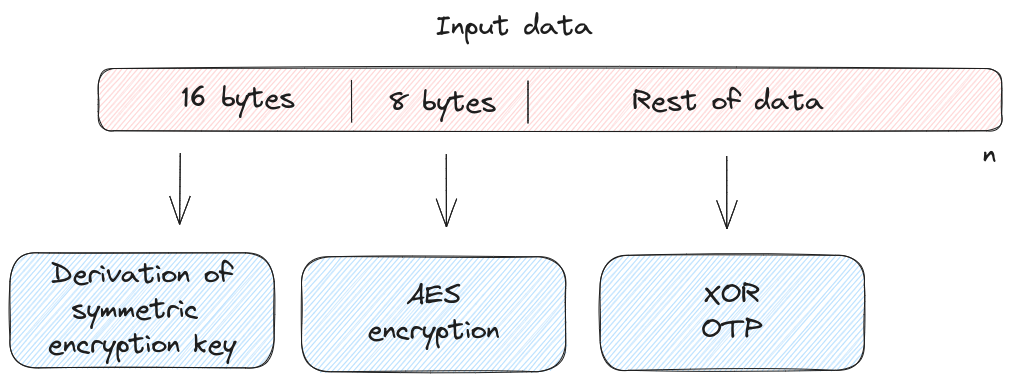

The two “Crypto” blocks in the diagram above implement exactly the same cryptographic algorithm using different constants and inputs and they can be further broken as follows:

- Derivation of symmetric encryption key for AES encryption

- AES encryption

- XOR with One Time Pad

Each one of these steps consumes part of the input data, either QR code or Transaction Data:

- Derivation of symmetric encryption key consumes input data

[0:16]. This step has a transitive dependency on the key material present on the device. - AES encryption consumes input data

[16:24], which is combined with an increasing counter to obtain a ciphertext whose length matches the one of the input data minus[0:24] - XOR OTP consumes input data

[24:]

In summary:

All cryptographic operations are implemented by SCOtpManager class, in java_src/net/aliaslab/securecallotplib/SCOtpManager.java and imported libraries. I’ll leave aside from this post the analysis of

the View logic as SCOtpManager and dependencies are sufficiently self

contained that do not need to interact with the UI

Key material stored on the device

A foundamental requirement for a 2FA device is that the OTP cannot be generated without the device itself. This seems to be obvious, but one of the reasons I wanted to reverse engineer the application was also to verify that the PIN alone would not be sufficient to get the OTP. There must be “something I have” involved, not just something I know.

Looking through the code, one can see that the application has a dependency over Android KeyStore and it implements

a two level key hierarchy. First, a SecretKey is retrieved in smali_classes4/v2/a/a/m.smali|e():

const-string p1, "AndroidKeyStore"

invoke-static {p1}, Ljava/security/KeyStore;->getInstance(Ljava/lang/String;)Ljava/security/KeyStore;

move-result-object p1

const/4 v0, 0x0

invoke-virtual {p1, v0}, Ljava/security/KeyStore;->load(Ljava/security/KeyStore$LoadStoreParameter;)V

sget-object v1, Lv2/a/a/m;->a:Ljava/lang/String;

invoke-virtual {p1, v1, v0}, Ljava/security/KeyStore;->getKey(Ljava/lang/String;[C)Ljava/security/Key;

move-result-object p1

check-cast p1, Ljavax/crypto/SecretKey;

On the read path, this key is used by smali_classes4/v2/a/a/m.smali|<init>() to read sealed objects

within a file. After retrieving the key, smali_classes4/v2/a/a/m.smali|c() is called to read and unseal the data:

invoke-virtual {p0, p1}, Lv2/a/a/m;->e(Landroid/content/Context;)Ljavax/crypto/SecretKey;

[...]

invoke-virtual {p0, p2, p1}, Lv2/a/a/m;->c(Ljavax/crypto/SecretKey;Landroid/content/Context;)Ljava/util/HashMap;

Code of smali_classes4/v2/a/a/m.smali|c() reveals the structure of the sealed objects. An IvParameterSpec is first fetched and used to inizialize the corresponding Cipher:

invoke-direct {v1, p2}, Ljava/io/ObjectInputStream;-><init>(Ljava/io/InputStream;)V

[...]

invoke-virtual {v1}, Ljava/io/ObjectInputStream;->readObject()Ljava/lang/Object;

move-result-object v2

[..]

new-instance v3, Ljavax/crypto/spec/IvParameterSpec;

invoke-direct {v3, v2}, Ljavax/crypto/spec/IvParameterSpec;-><init>([B)V

iget-object v2, p0, Lv2/a/a/m;->j:Ljavax/crypto/Cipher;

const/4 v4, 0x2

invoke-virtual {v2, v4, p1, v3}, Ljavax/crypto/Cipher;->init(ILjava/security/Key;Ljava/security/spec/AlgorithmParameterSpec;)V

Then, a hashmap containing device keys is read:

invoke-virtual {v1}, Ljava/io/ObjectInputStream;->readObject()Ljava/lang/Object;

move-result-object p1

check-cast p1, Ljavax/crypto/SealedObject;

iget-object v2, p0, Lv2/a/a/m;->j:Ljavax/crypto/Cipher;

invoke-virtual {p1, v2}, Ljavax/crypto/SealedObject;->getObject(Ljavax/crypto/Cipher;)Ljava/lang/Object;

move-result-object p1

check-cast p1, Ljava/util/HashMap;

The hashmap stores three values:

sc_sacsc_k2sc_id

with only the first two actively used for cryptographic purposes. AES key derivation happens in two steps, with an “Intermediate Key” first generated from key material on the device as a concatenation of the following contributions:

- A key derived from

sc_sac, which we will refer to asIK(sc_sac) - A key derived from

sc_k2, which we will refer to asIK(sc_k2) - A constant, which differs between QR Code,

IK(const_qrcode), and Transaction Data,IK(const_tdata). In the former case, it is pre-pended to the first two contributions, while in the latter case it is appended.

Overall, IK structure for QR code can be summarized as follows:

IK = IK(const_qrcode) + IK(sc_sac) + IK(sc_k2)

while IK structure for Transaction Data can be summarized as follows:

IK = IK(sc_sac) + IK(sc_k2) + IK(const_tdata)

The following three sections give an overview of how each component of IK is derived.

Derivation of IK(sc_sac)

The piece derived from sc_sac is the most complex one and it is the result of a sequence of

transformations shown in the following diagram:

sc_sac [1] is first combined [2] with a use case specific fragment [3].

The combination process is implemented in smali/n2/a/a/f.smali|<init>() [code] and it is relatively simple

to understand directly from smali code:

aget-char v6, v1, v4

mul-int/lit8 v5, v5, 0x1f

add-int/2addr v5, v6

add-int/lit8 v4, v4, 0x1

One can notice that the fragment is passed as string agument. A more friendly Java equivalent could be the following:

int i2 = 0;

for (char c : str.toCharArray()) {

i2 = (i2 * 31) + c;

}

For QR code operations, the fragment is sc_k2[0:5] [code], while for Transaction Data user PIN is

used [code]. The resulting key [4] then encrypts [5] 16 null bytes [6] [code] and the ciphertext [7] is further

shifted [8][10] to obtain two more patterns, c2 [9] and c3 [11].

The trailing bytes of the fragment [3] which exceed len(fragment)%16 are XOR-ed [13] with either c2 [9] [code] c3 [11] [code], depending on the value of len(fragment)%16. The result is encrypted [14] [code] with the null

bytes encryption key [4] to obtain a final ciphertext which constitutes IK(sc_sac) [15].

In the diagram above the null-bytes encryption sequence is highlighted as it will be re-used also for the AES key derivation process.

Derivation of IK(sc_k2)

sc_k2 is XOR-ed with time deltas [code] and appended to the initial part of the intermediate key.

The presence of a dependency on

Unix time is immediately obvious by reading top level decompiled code from SCOtpManager class:

int currentTimeMillis = (int) (System.currentTimeMillis() / ((long) 3600000));

arrayList.add(ByteBuffer.allocate(4).putInt(currentTimeMillis).array());

for (int i2 = 1; i2 <= 2; i2++) {

arrayList.add(ByteBuffer.allocate(4).putInt(currentTimeMillis + i2).array());

arrayList.add(ByteBuffer.allocate(4).putInt(currentTimeMillis - i2).array());

}

The time deltas have a 1 hour granularity (ms/3600000) and the application attempts to combine sc_k2 with [-1,0,+1] added to the current time. Note that this obviously does not constitute in any way a mechanism to force input data to expire. The application does fail to produce a valid result outside of the [-1,0,1] time window,

but this only a limitation of client side logic and one can choose any time adjustment constant [code].

Derivation of IK(const_tdata|const_qrcode)

Depending on whether we are working with QR code or transaction data, the intermediate key is further combined with the following:

- For QR code, a constant correponding to

0x6ab392fd02is pre-pended [code]. This is value is hardcoded - For transaction data, a constant of

0x8000000000[code] is appended

AES key derivation

The AES key derivation process is implemented in smali/n2/a/a/a.smali|b(), with the actual input

parameters coming from java_src/n2/a/a/a.java|a(). The overall algorithm is shown in the diagram below, with the null-bytes encryption sequence being very similar to the one used to generate IK(sc_sac):

Two inputs are given:

- The intermediate key, IK [19] [code,qr] [code,tdata]

- The first 16 bytes of input data [16] [code]

The 16 bytes are XOR-ed [17] with a constant whose value is use case dependent [18].

QR code operations use AliasLabAliasLab [code], while L=T=1W:JCFLSKH3B [code] is used for transaction data.

Interestingly, these constants are not static values defined in code, but rather they are calculated algoritmically at runtime in smali/n2/a/a/c.smali|<clinit>() [code].

There is no source of randomness nor any input given to the algorithm, so the output is always the same.

The result of the XOR operation constitues the fragment whose trailing bytes are XOR-ed [28] [code] with the constants [24][26] obtained from the null bytes encryption sequence executed with IK [19] as encryption key in this case.

The variation with respect to the algorithm that derives IK(sc_sac) is that the final XOR with c2 and c3 [28] and AES encryption

steps [29] are repeated multiple times [code] (5000) and at each step the output value is

accumulated through XOR operation with the previous results [code].

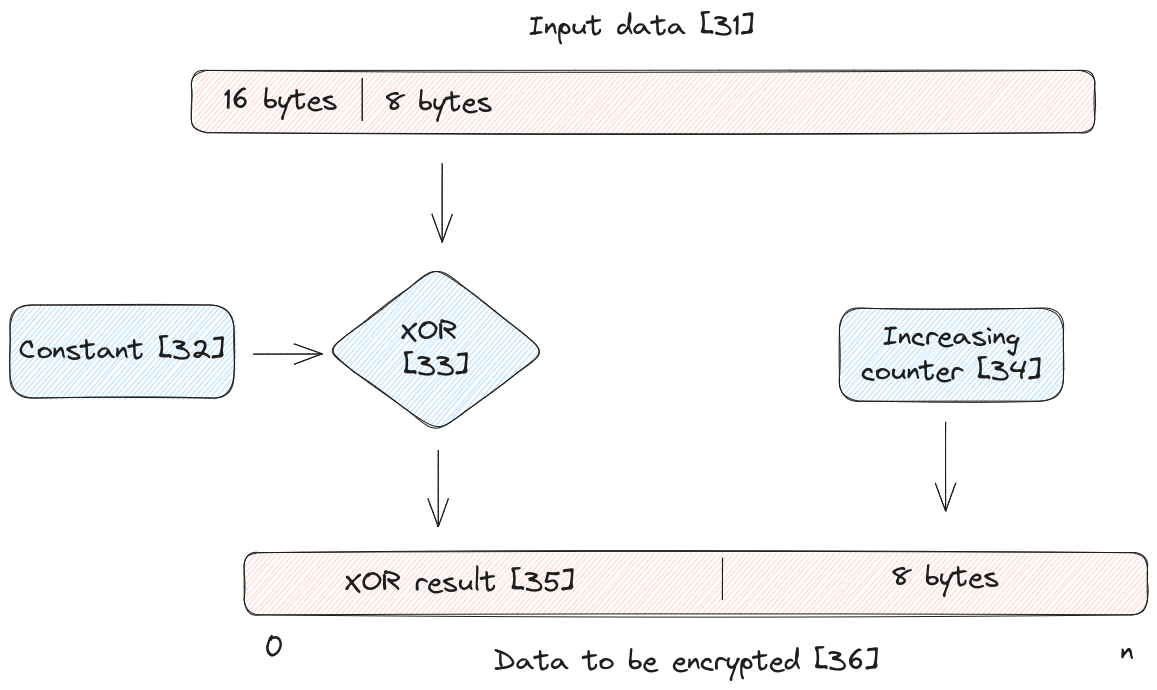

AES encryption

The AES encryption step, summarized in the following diagram, produces the byte stream that when XOR-ed with the One Time Pad generates the plaintext.

The ciphertext is generated

from bytes [16:24] of the input data [31], which are tranformed as follows:

- Input data

[16:24]is XOR-ed [33] with the same constants [32] we have encountered for AES key derivation [code] - An increasing counter [34] is copied in upper 8 bytes of the XOR-ed value [code]

As an example, consider the following QR code:

5CF8EAAD1F91CD0FD3519153A077E26DCC2F8B57A545E1C7D4301EAD6860E766A2C799AB56D7FB3EDFE1636AC9ACC55CF8EAAD1F91CD0FD3519153A077E26DCC2F8B57A545E1C7D4301EAD6860E766A2C799AB56D7FB3EDFE1636AC9ACC51A364A300C27F27E28E893ADBEE4C547AD0C8376C033E685170E4402B1F1E63E62A2711B7530B90D3A97D771D1BC991CD9A39586A61AF81B2F4E2D728CBB0BDF73C518244AEDA4CC79A72DAEF8FCF40314F95ED86F560C35408FF46E0272E8A0F031AE73B23CFCA0D4FC0996209D40440BF349482974A4176EA6F10D03901D05F779C606AD2FAB8B971F649852A98EDBB45C2706AE17E52FE3A0DB3510E3F857FE17AFCD0086B7A933DBA647A0598C9F5F077DEC05B5E3247ADC5056F3ED2E6A5E4AA8A7AFFD4128C9544C19D27A9B4332CAD7353B11C2541B206A5C7752CFF989D4B5E8FF491780766583BF0AE65AE4710AC7B1F1FE9E07B36327FDFB28227B477FE53C9615ADF904DAE2972C17DEF1797307ECA6EB9C28D4345E4DE65C47FC3095267EF0DB87D820DB0442DD6648703F35F65BE2B218D2B91D9AA6550D81A930B1ABEF009699061BBDCEA83392A36AE3DC30B4

If we extract bytes [16:24] from input data, we obtain:

CC2F8B57A545E1C7

Since we are working with QR code data, the XOR constant is AliasLabAliasLab, i.e. 416C6961734C6162416C6961734C6162. QR code bytes are XOR-ed for the common length:

CC2F8B57A545E1C7 ^ 416C6961734C6162416C6961734C6162 = 8D43E236D60980A5

The increasing counter is copied in the upper 8 bytes of the 16 bytes result array, while the XOR-ed value is copied in the lower 8 bytes, resulting in the following:

8D43E236D60980A50000000000000000 with counter = 0

8D43E236D60980A50000000000000001 with counter = 1

8D43E236D60980A50000000000000002 with counter = 2

[..]

Each of this fragment is then AES encrypted with the AES encryption key. This process is repeated to obtain enough 16 bytes arrays to match the length of input data, either QR code or Transaction Data.

XOR-ing with One Time Pad

The final operation which yield OTP secrets consists in XOR-ing input data [24:] (we have already

used 24 bytes, for AES key derivation and plaintext calculation) with the encrypted fragments obtained in the previous section.

Closing thoughts

Before diving into this reverse engineering exercise, I only had a high level understanding of RFC 6238 and it took just ~30 lines of code using only crypto primitives for a basic implementation compatible with google-authenticator:

secret := "<secret>"

byteSecret, err := base32.StdEncoding.DecodeString(secret)

if err != nil {

panic("decoding byte secret")

}

hasher := hmac.New(sha1.New, byteSecret)

t := time.Now().Unix()/30

buff := bytes.NewBuffer(make([]byte, 0))

binary.Write(buff, binary.BigEndian, t,)

hasher.Write(buff.Bytes())

hmacHash := hasher.Sum(nil)

offset := int(hmacHash[len(hmacHash)-1] & 0xf)

code := ((int(hmacHash[offset]) & 0x7f) << 24) |

((int(hmacHash[offset+1] & 0xff)) << 16) |

((int(hmacHash[offset+2] & 0xff)) << 8) |

(int(hmacHash[offset+3]) & 0xff)

code = code % int(math.Pow10(6))

otp := fmt.Sprintf(fmt.Sprintf("%%0%dd", 6), code)

fmt.Printf("OTP is %s\n", otp)

The main logic of bank-otp-gen consists of ~350 lines of code. This implementation seems to be unnecessarily complex and more importantly, unnecessairly diverging from far simpler industry standards. Keep things simple, especially when working on security-critical pices of the infrastructure.